DRUID WAYS AND LONDON'S LEYS

part II

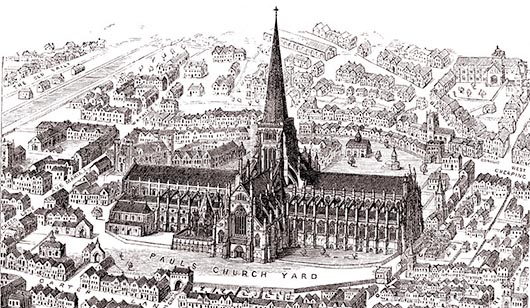

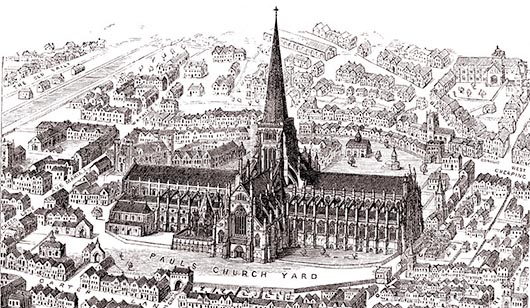

Old St Paul's Cathedral, London. Built on the former site of a temple dedicated to Diana.

Old St Paul's Cathedral, London. Built on the former site of a temple dedicated to Diana.

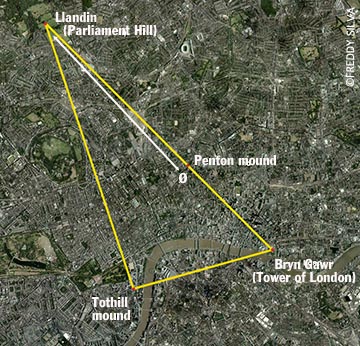

It appears the sacred stone’s well-being really is linked to that of the city. But its story does not end there, for when one aligns it with its attendant stone circle – now marked by St. Paul’s Cathedral – a ley line can be drawn that connects to another nearby sacred mound, the Tower of London.

Despite its macabre image as the world’s most notorious prison, the central feature of this site was once called Bryn Gwyn, a Welsh name meaning ‘white or holy hill’. Like others of its kind, the connotation with ‘white’ refers to the mound as a place of veneration of the Light, the Sun. If the conical mound was built by Brutus, as is alleged, then its deliberate alignment to its two nearby sacred sites, and the subsequent triple alignment to the winter solstice Sun, is evidence that homage was paid by the Trojan warrior to the overarching religious principle of the land, and that the sacred foundations of the area were to be continued. Brutus appears to have understood the importance of sacred alignment, as well as the ancient tradition of anchoring subtle energy to bring beneficial effects upon the land and its people, for when he died c.1100 BC he asked to be buried in the conical hill so his presence in the mound would offer protection to the future citizens of London. A number of subsequent kings continued the tradition, and like the London stone, it was said that so long as the remains were left undisturbed, London would remain safe.

One such king was the fabled Welshman, Bran the Blessed. After falling to a poisoned arrow he ordered that his head be buried in the Bryn Gwyn: “And they buried the head in the White Mount, and when it was buried this was the third Goodly concealment; and it was the third ill-fated disclosure when it was disinterred , inasmuch as no invasion from across the sea came to this island while the head was in that concealment.” The symbolism behind the decapitated head was simple: the head contained the soul and the soul was a particle of God, a hologram of the ultimate Creative Force, therefore to add the head of a great leader or religious person to a mound served to accentuate the energy of place, for the sacred mound was itself the head of the body of the land, the point where the Earth’s magnetic forces congregate. This ‘cult of the head’ lasted for millennia and its importance was still felt with the decapitation of John the Baptist, whose head was venerated by the Knights Templar. In essence, the practice was a continuation of the pagan green man, whose head spewing forth vegetation is found carved more often throughout English churches than statues of the Virgin Mary.

Like the fate associated with the aforementioned menhir of London, when Bran’s head was removed from the mound Bryn Gwyn, Britain was indeed invaded, by William of Normandy, who proceeded to built his White Tower upon the sacred mound, henceforth to be known as the Tower of London. Since then, the ravens that inhabit the site have had their wings clipped, for it is said that if the black birds leave the Tower, so the fate of England will follow. Interestingly, raven in Welsh is bran.

William the Conqueror was certainly not an ignorant man nor a mere warlord, but one of the last monarchs to fully understand the meaning and implications of asserting one’s power upon an ancient mound of veneration. And when he built his seat of power upon this most ancient of London’s sacred mounds he was asserting his will upon an entire country. Interestingly, he consecrated the site on the Summer Solstice, once again continuing the tradition of venerating the hill of Light – a process he repeated at other sacred mounds during his campaign through England.

The London Stone at St. Swithin's after the war.

Returning to the site of present St, Paul’s cathedral, a few yards northeast of the original stone circle stood a Druidical Sanctuary, a kind of college where the ancient mysteries would have been taught by committing important facets of universal wisdom to memory, some candidates requiring no less than twenty years to learn the teachings and recall them at will, and accurately. The Sanctuary and the circle were later merged, and in recent historical times it became the Christian Sanctuary of the Collegiate Church of St. Martin-le-grand. Clearly this area was of great importance, but by no means the only one in London, for a second stone circle used by the Druids, along with an adjacent College and Sanctuary, existed two miles to the west, on Island the Thorns. The only remains of the site are preserved in the place names: Great College St., The Sanctuary, The College Garden. And although the sacred mound has been obliterated, its processional causeway is commemorated by Tothill Street – tot meaning ‘sacred mound’ – the precise location being Tothill Fields, a small, grassy meeting place sitting between the street and the majestic building now placed to its east, Westminster Abbey, still the place of proclamation of kingship in Britain.

Like the Bryn Gawr mound two miles to the east, it was associated with Brutus the Trojan, but its fate was less fortunate and survived only up to the 18th century. That the mound still stood during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I is evidenced by the topographer of the period, who wrote, “Tootehill Street, lying in the west part of the cytie, taketh name of a hill near it which is called Toote-hill, in the great feyld near the street.” It is an estimation of this Druid site’s importance that the English Parliament should have been built adjacent to it and nowhere else in London. Indeed, the location is the very nerve center of power in England, surrounded as it is by central government buildings and law courts as well as foreign embassies.

Geometric relationship between the four London mounds.

What is fascinating about the position of the three conical mounds – Bryn Gawr, Tothill and the original Llandin – is that they form a perfect right-angle triangle to within one degree of accuracy.

The ancients were obsessed with arranging sacred sites in either right-angle, isosceles or equilateral triangles, one reason being that the shape is a representation of the sacred trinity, the most powerful creative force of the universe.

The triangle is also a flattened representation of the tetrahedron, the four-sided pyramid-like lattice structure upon which all molecular structures are based. It is the glue of God. Thus by associating the shape with the position of temples, the sites – and the people who entered them – would be imbued and blessed with this etheric energy.

Continue to part III

Return to Articles

Perfect ley linking the mounds of Silbury and Tower of London, referenced by the Eton-Windsor mounds, which act as a 'doorway'.